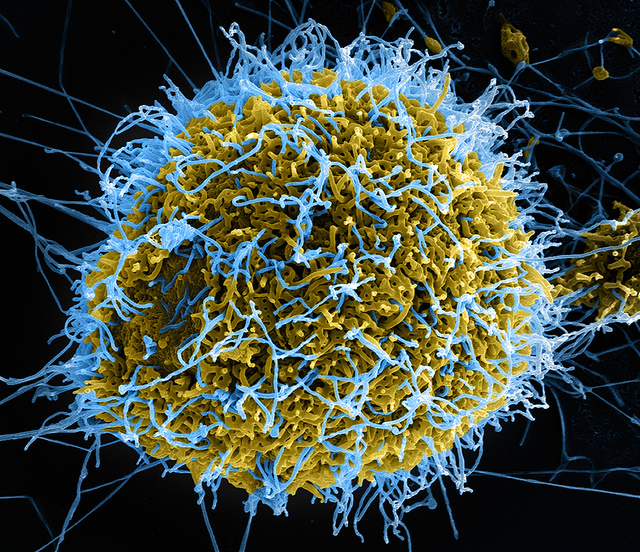

A leading epidemiologist and governor of the Wellcome Trust has said there were “obviously parallels” between the Medical Innovation Bill and the sanctioning of untested therapies for Ebola patients.

Prof Peter Smith was on the World Health Organisation’s panel which permitted the use of untested therapies for the fatal Ebola virus.

Prof Smith said the WHO panel’s guidance “gave the go-ahead to use products for treatment that were not licensed for treating Ebola.”

Prof Smith said there were similarities between the Medical Innovation Bill and WHO Ebola Guidance.

“There are obviously parallels,” he said. If I had a cancer that say had a 70% mortality in six months and there was an experimental therapy and there’s no data on it, but which might actually improve that survival – and it looked at if it wasn’t going to kill me tomorrow – then I might well want the opportunity of taking that drug or whatever it was. And that’s the situation the Ebola patients are in.

“I think the situation here [with Ebola] was sufficiently dire that there was encouragement to actually shortcut the normal processes. I mean, to use therapies for which there may not be as strong an evidence base with respect to safety as you would normally require – but these were special circumstances.”

Another parallel with novel Ebola treatments and the medical Innovation Bill is the idea that in cases where a full trial is impossible – for lack of patient numbers, or because of an imminent likelihood of the death of the patient, innovative treatments could form the foundation of a full trial at a later date.

He said while it was impossible to draw sound data from a small number of cases, such innovations would “at least produce the evidence needed to justify doing a proper trial.”

“Treating a small number of patients with a new therapy, can’t make that judgment with any confidence in a small number of patients but at least it will produce the evidence needed to justify doing a proper trial. One of the strategies that’s being used for the new Ebola treatment is to really just do that.”

Acknowledging there was a risk in prescribing treatments that had not been through full clinical trials, he added: “You don’t want to give [patients] treatments that would hasten their mortality but you’re more inclined to take that chance because they’ve got this severely life threatening condition anyway.

“The mortality rate is still very high and there’s really nothing on the shelf that is licensed to treat these conditions and that, I think, is the incentive to use things which have been either been slow to being developed or really are experimental.

“These [treatments] might have worked against other viruses but one doesn’t know if they’re going to work against this virus. Obviously you’re prepared to take more risks with respect to something that is going to be given to someone who has quite a high chance of dying anyway than you would in someone who is perfectly healthy.”

However, Prof Smith said novel treatments should only be used in the best interests of the patient – and not as mini-experiments.

“If you are giving a certain therapy to a patient then you have to believe it’s going to do them some good. But you may do that with considerable doubt as to whether it will actually will do them good – but you have to believe it will do them more good than harm.”

As with the Medical Innovation Bill, which will require a mandatory reporting of the results of medical innovations – something that does not happen at the moment – Prof Smith said doctors using novel Ebola therapies should also collect data. “You should maximise the information you get out of that and measure as much as you can even though it’s not a formal trial.

2 thoughts on “Why Ebola treatment has parallels with the Medical Innovation Bill”

Comments are closed.